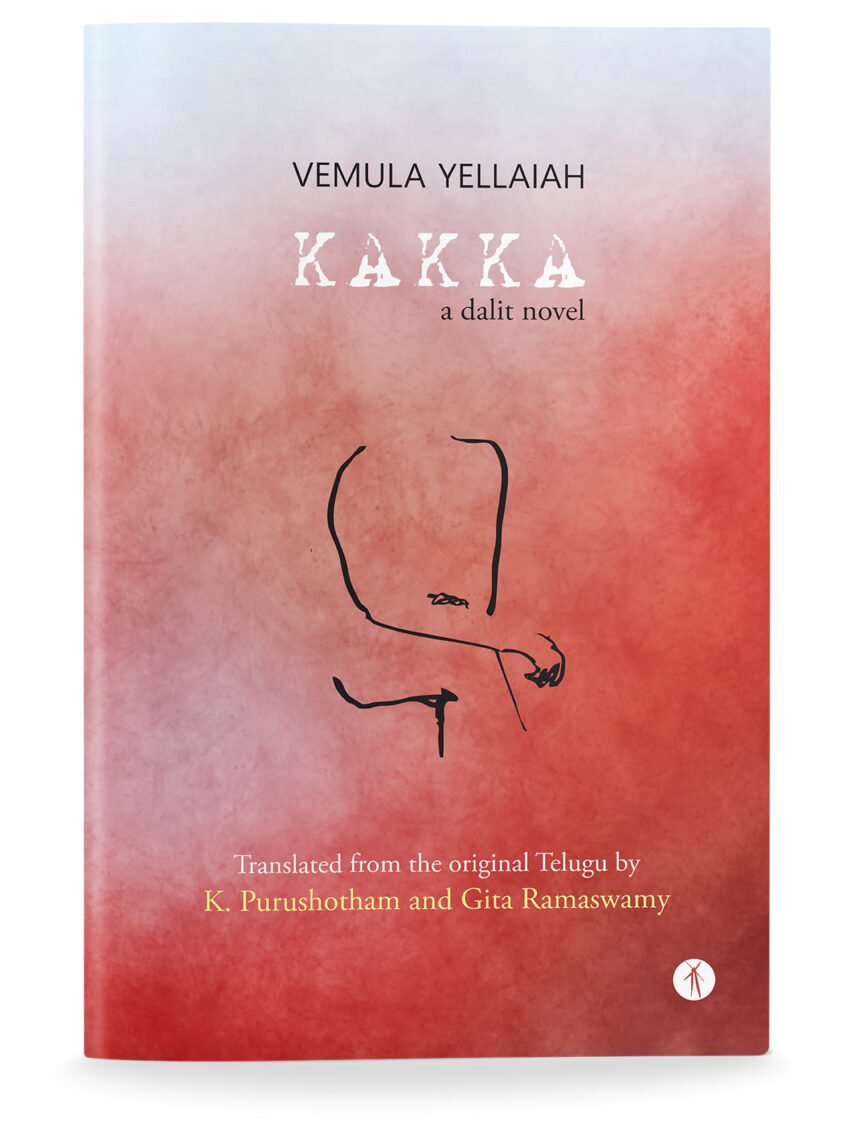

Kakka by Vemula Yellaiah

By: Mani Rao

Here are some notes after reading Kakka. They are not meant to be comprehensive, nor like a review (with a summary, explanation of the significance of the book, and a critique).

If readers wish to gain a perspective on Telugu Dalit literature, they may read K. Purushotam’s essay “Evolution of Telugu Dalit Literature” published in Economic and Political Weekly, and which is available on JStor. If that is not accessible, Sai Priya Kodidala’s article in First Post is available online. Kakka contains an informative Afterword by the translators, where they note that Kakka, which was first published in Telugu in 2000, is the first novel by a Dalit author from Telangana to be translated into English.

In this note, I focus on the skill of the author.

Throughout the book, the author’s hand is light, and pathos emerges from plot development. I contrast this with Arundhathi Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, a book so packed with authorial commentary that it is a struggle to read. Yes, of course, Kakka draws a picture of Madiga life under the oppressive thumb of history and continuing human exploitation. In this hierarchy of caste and sub-caste, suffering is most intense at the bottom. But – and therein this book succeeds – there is no group singled out as villain.

Caste groups act against each other, but they also work together—a Dakkali person picks auspicious names for the Madigas, a Muslim suggests how a Madiga can become the village chief. Even a typical character like Patel evolves.

I see two climactic scenes in the book—Kalemma’s trial, and Kakka fending off wolves. In the first, Kakka’s mother Kalemma is ex-communicated based on false allegations and just when her plight is just about to break the reader’s heart, the story turns—she is remarried and never shows up again in the novel. Kalemma has played her role in shaping and strengthening Kakka, and the story moves on. The plot reaches another crescendo when Lasmakka delivers a baby in a cart on the way to town. Two symbolic events occur almost at once—Kakka sees a snake about to prey upon baby birds, and attempts to be their savior. At the same time, he has to fend off wolves who have come to the scene sniffing the placenta. He becomes larger than life by taking on the persona of Mahisasura, a character he has enacted in a play. The symbolism is evocative– only excessive effort can help Kakka contend with his situation.

Land is very much the foundation, or stage, of the novel. It is when Kalemma wishes to sell her share of the Madiga well that Agamaiah harasses her. Kakka’s persistence stems from the fact that his ancestors’ placentas are buried in this land. Kakka is heroic at the end because he successfully plants his newborn’s placenta in an anthill.

In the last chapter, the author provides a synopsis of events and context through the voice of Kakka. Technically, this may count as a spoiler, but this is actually helpful and has a zooming out kind of effect.

At a bleak point in the plot, when there has been a failure of togetherness, the story ends abruptly, as if with a sublimated pain. Here are the last two lines of the book:

“The lad pissed in fear; the blood the father shed and the urine the lad pissed, together made a puddle on the floor. Looking at this, they indulged in a wrangle, wailing and laughing, as though they had seen something in it.” (p.214)

Ultimately, it is art that expresses both rebellion and joy. Pakir-thatha tells Kakka how to skin dead animals and make leather–

“we have to treat the skin as though we are taking care of a mother who has just delivered a baby” (p.82).

Listening in along with Kakka, the reader gains insight and respect for the work and art of the community. The narrator tells us that the farmers “sang songs to fight exhaustion” (p.53) and by means of a single line in the song lyrics, illustrates the pathos and grim reality of the situation— “your character is the worst//we will not survive without work.” And finally, Kakka surpasses himself through the role of Mahisasura in a street play.

The Telugu novel was written in Madiga dialect, a statement in itself, declaration of revolt, or assertion, against conventional Telugu literature. The translators explain in the foreword that there is no way to capture the specific register and differential from the standard language. They are even apologetic—“The English reader will miss dialect, orality, register and other forms of subversion like syntax and punctuation in the original Telugu” (v). But, in fact, the translation is already successful because the very content creates the distinction. Here are two casual, even random examples. “May the wife of the girl be fucked” (87). “Ayya, even if you slit our stomachs you will find that we have no intestines” (125). “Swearing by the sneeze, I speak the truth” (didn’t note page number). Speech patterns are conveyed by the simple, inventive insertion of words that convey tones —“Ehe,” “Arey,” “Aa” — and mind you, these are not in italics. Overall, a language that is both unique as well as understandable.

Book Details:

Kakka: A Dalit Novel by Vemula Yellaiah

Translated by K.Purushotham and Gita Ramaswamy

Publisher: Hawakal, India, 2021

For purchase:

https://www.hawakal.com/books/bags/kakka-a-dalit-novel/

Leave a Reply