Tales of the Prince Charming of Indian Cricket

(This article is being published on the second death anniversary of Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi)

Last week’s mail included a packet from my brother who recently returned from India. It contained a book with an attached hand written note saying,

Bro,

You Like

* Books

* Cricket

* MAK

Enjoy.

Thanks Anil, I did. A lot.

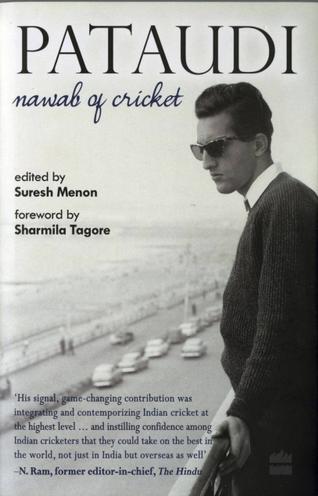

The book was Pataudi: Nawab of Cricket, an interesting and delightful collection of 24 reminiscences about the late Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi (5 Jan 1941 – 22 Sep 2011), and a foreword by Sharmila Tagore. Suresh Menon, who wrote several books on Indian cricket, edited this book. Some of these were written after his passing away, but there are some that are quite old, including one by Vijay Merchant, (yes, the very one) written in 1966.

These friends, fellow players, family members and fans bring up several facts about the late cricketer that I was not aware of. Mansoor Ali Khan descended from Ali Khan, who came from Afghanistan in the sixteenth century at the time of Akbar. One of his ancestors was conferred the title of Nawab of Pataudi in 1806 as the ruler of 20,000 people, with a grant of a state of 52 square miles, about 35 miles southeast of Delhi. On his eleventh birthday, Mansoor Ali Khan lost his father, Iftikhar Ali Khan, the then Nawab of Pataudi, a renowned cricketer who represented both England and India; he died in the saddle while playing polo. As a six year old, Mansoor Ali Khan was given a gun and placed at a window and asked to guard his ancestral home (presumably during the partition days). His mother was the Begum of Bhopal and he inherited the title to both the states, until they were taken away from him with the abolition of privy purses in 1971.

David Woolley’s essay, drawing from the Wisden and the Winchester College school magazine, The Wykehamist, gives a detailed account of Tiger Pat’s schooldays from the time he took the field in grey (apparently, one has to qualify for the white flannels) for the school in 1955 till the time he captained the school team in 1959, scoring 1068 runs in the season with an average of 71.2. He began playing county cricket for Sussex in 1958 (he picked Sussex and not his father’s team Worcestershire, probably because the cricket master at Winchester, Hubert Doggart, was a former captain of Sussex). The correspondents of the day note that this young man had ‘aeons of time’ in which he picked up the bowling. This is a theme that recurs in other essays as they deal with his exploits for Oxford and Sussex, before the fateful accident. Many people believe that this was a physical gift he lost because of the accident and that he would have been a phenomenal batsman had he not lost sight in his right eye. (Sharmila Tagore says that he would never raise that subject and would get very annoyed at any speculation about what his batting average might have been had the accident not happened).

Pataudi got admitted to Balliol College in Oxford. Ted Dexter notes that Pataudi must have ‘had brains’ to get admitted to the Winchester school and the Balliol College at Oxford. At Oxford, he continued his exploits with the bat. He hit a century against Cambridge. He had centuries in both innings against Yorkshire, showing scant respect to Fred Trueman.

Young Pataudi’s exploits with the bat at Oxford were apparently followed keenly back home and the cricket savvy were salivating at the prospects of the young man bringing glory to India. Naseeruddin Shah, famous actor and a fan, writes about collecting the picture of a ‘dapper young Oxford player executing a graceful sweep shot’ with the legend, ‘The new captain of Oxford, the Nawab of Pataudi, on his way to a century against arch-rivals Cambridge.’ N. Ram’s essay quotes the young Nawab’s batting exploits at Winchester and Oxford from articles in Sports & Pastime and The Hindu, respectively in 1958 and 1961.

There are several descriptions of the accident in this book. Abbas Ali Baig, the dashing batsman that represented Hyderabad and India, was his teammate at Oxford and was one of the people that rushed to the accident site and found Tiger lying on the ground by the car. Minutes earlier, Tiger decided at the very last moment to get out of the team van and travel in a car. Robin Marlar notes that the other Oxford cricketer injured in that accident, “the driver Robin Waters, a gifted young wicket keeper, paid a devastating price, as I understood forty years later when we met at a Sussex match in Dublin where he was boarding in a religious house. His deep scars were mental.”

Pataudi dealt with it in a different manner. He told his daughter Soha later, ‘I lost sight in one eye, but did not lose sight of my ambition.’ He was back at the nets within 3 or 4 weeks, rehabilitated himself with a determination and made his debut for the Indian cricket test team within six months of the accident. Because of another accident on the cricket field barely two months later, he became the youngest captain in test cricket history, after playing only three tests. He, however, was doing this, playing with only one eye; despite his acclaimed prowess as a fielder, he had trouble throwing for the next five years. In 2001, young Saba Karim, a wicket keeper for India was hit in the eye. As Tiger was helping him accept his fate, Saba asked him how long it took him to recover. ‘Saba,’ he said, ‘I never recovered’. In an interview with Mike Coward, he recounted that it took a bit of doing for him, ‘…to accept that I was thirty to forty percent below what I would like to have been.’

Many cricketers including Bishen Singh Bedi and Farokh Engineer (as do other players quoted in some of the other essays including Prasanna and Chandrasekhar) talk about Mansoor Ali Khan’s contributions to the Indian cricket team – ‘bringing the culture of Indianness to the team,’ integrating the various parochial and religious identities that the players carried unto then, his leadership by example demonstrating to his teammates that they are as good as any of the white players, his original idea of using the spin quartet as an offensive weapon for India, and his emphasis on improving the fielding.

N. Ram of Hindu writes the longest (24 pages) and the best researched article in the book, Time of Tiger. Ram was The Hindu’s cricket correspondent covering Tiger’s last series, against West Indies in 1974-75 (I don’t recall his byline, but I must have read his reports those days).

Vijay Merchant, in his 1966 article in the Illustrated Weekly of India, The Prince Charming of Indian Cricket, writes adoringly of the batting prowess and the captaincy skills of the young Nawab of Pataudi, whom he credits as the one person responsible for the then happy state of affairs in Indian cricket. ‘After a long time in our cricket, we found the right man to lead India.’ Within the article, Merchant fondly recalls his association with the senior Nawab of Pataudi (rumor had it that Vijay Merchant carried a grudge against the Pataudis for being passed over for the captaincy by the senior Nawab) and says, “I had the privilege of playing under his late father in 1946 in England. If I were twenty years younger, I would be most happy to play under Mansur Ali Khan of Pataudi.” Merchant recalls the father, during the 1946 tour of England, ordering Messrs. Gunn & Moore Ltd. to prepare a special autograph bat for a six-year old child. Merchant’s article ends with the following – “This then is the story of India’s captain – the youngest in international cricket – a captain presented to this country by the casting vote of the chairman of the selection committee. Thanks a million, Mr. Chairman!” (Five years later, Vijay Merchant’s casting vote as the chairman of the selection committee removed the very same captain). ‘Politics in India kept out many a good cricketer and brought about the premature retirement of quite a few,’ wrote Merchant, ‘It is my sincere hope that Pataudi, who has kept himself above party politics, partisanship and favoritism, will be allowed to continue to lead India as long as he can retain his place in the side.’ Speak of irony.

An interview quoted by N. Ram refers to some difficulties that Pataudi, the captain, had with Vijay Merchant, the chairman of the selection committee. In that interview (not in this book), Pataudi said that he couldn’t understand why he was denied (by Merchant) the players he wanted during the 69-70 New Zealand and Australia series though the same players were picked up after he was removed as the captain.

Muder Patherya, who worked in Sportsworld under Pataudi, talks about the many facets of Tiger’s personality that he got to witness. However, his piece is remarkable for his candid assessment that, based on statistics alone, Pataudi could not be considered a great batsman or a great captain. But, he is quick to add how Pataudi’s captaincy transformed the Indian cricket and paved for the success that followed his tenure.

Ian Chappell writes about his difficulty in figuring out what princes do (‘Ian, I’m a bloody prince.’). And, Sunil Gavaskar writes about his difficulty in figuring out how to address a Nawab that plays cricket alongside him. Pataudi did not answer Gavaskar’s question as how he should be addressed, and Gavaskar says that he just spoke to him without calling him anything. It appears that during his younger days, he was often referred to as Tiger and the Noob, and as Pat in later days.

Sharmila Tagore’s loving portrait of the man that she loved and married describes his zest for life, wit, sense of humor, gentleness, maturity at an young age, love of music and his determined fight till the end. Daughters Saba and Soha write about their Abba, who apparently was surprisingly frugal.

Some other things I learned reading this book:

Girish Karnad was a contemporary of Pataudi at Oxford.

Pataudi was good at squash, hockey and cycle polo. He had a serious interest in music and could play several instruments including tabla, sitar and harmonium. He was friends with Lata, Asha, Talat Mahmood.

While everybody talks about Pataudi losing his captaincy due to a casting vote of the chairman in 1971, he apparently was the beneficiary of a casting vote by the chairman M. Dutta-Ray when he was continued as the captain for the 63-64 home series against England.

Pataudi had to fight to get GR Viswanath included in the Indian team when he made his debut against Australia in 1969.

Bedi, Chappell and others rave about Pataudi’s 75 and 85 at Melbourne Cricket Ground in a test match in 1967. He was batting not only with one good eye, but also with only one good leg. He had a pulled hamstring and wasn’t allowed a runner. But, he was hitting huge in the venue with the longest boundary in test cricket.

Pataudi never cared to carry a bat of his own. As he went to bat, he would pick up the bat nearest to the door of the dressing room. As a result, in the same innings, he would be seen playing with a different bat after each break. He used five bats in the first innings of that Melbourne test – a fine craftsman that did not need to give credit to his tools, says Farokh Engineer.

N Ram quotes from a May 1961 story in the Hindu (two months prior to the accident): ‘After two successive sixes, the young Nawab of Pataudi asked a fielder to pick a target. The fielder pointed to a car beyond the far boundary. ‘The next ball the Nawab smote plumb on the car roof.’

Pataudi was the first son to follow his father in Indian test cricket.

Like his father, he scored a century in his first appearance against Australia.

Tiger made his debut as captain against his favorite cricketer Frank Worrell with whom he had played deck games on ship as an eleven year old on his way to school in England.

Pataudi was terrified of flying and would take the train whenever possible. He would usually ‘tank up’ before boarding a flight.

In the old days, the visiting cricket teams would fly between venues, but the Indian team would travel by train (and miss practice time).

Pataudi used to be very concerned ‘of the genetic medical condition that carried off so many of his ancestors before they reached the half century.’

Pataudi was a prankster and known to prepare elaborate pranks.

The highly talented Hyderabad team of the 70s was more intent on having fun rather than on discipline – which might have accounted for its lack of success in Ranji Trophy. Abbas Ali Baig says that if there was a trophy for the team having most fun off the field, they would have won it hands down.

Gavaskar was mad about Jaisimha.

Farokh Engineer is bitter about being denied the opportunity to captain the Indian side (when Pataudi was sidelined due to injury) during the 74-75 West Indies series.

Rajdeep Sardesai, the political commentator, is the son of Dilip Sardesai, the cricketer.

Soha Ali Khan, the actress daughter, had a B.A. (Hons) from Oxford and an M.Sc. from the London School of Economics.

Mike Brearley, the former captain of the English cricket team, was the president of the Institute of Psychoanalysis, UK.

It appears that Pataudi was not swimming in money; he lost his title and privy purses (and his captaincy of the Indian team) at the age of 30. He moved from a sprawling three acre bungalow in Delhi to a more modest home. His privy purse in 1961 was about Rs. 48,000 per year.

The book has a very attractive cover of with a photograph of the young Pataudi in profile. The page opposite the title page had a reproduction of a news story (with a handwritten note to Rinkoo – Sharmila Tagore) about the Noob playing in rain with his raincoat on. I hoped for more such photoes inside and was disappointed. I could not figure out how Sharmila Tagore could have agreed to the color photograph of the couple in which he looks like Tinnu Anand and she, disinterested and tired. I have seen a dozen commercials for Gwalior Suiting that were infinitely better. The book is printed well.

There is a bit of redundancy in some of the information presented, but, I suppose, it is unavoidable when multiple people are writing about the same person. The quality of writing is also quite variable.

If you like books, cricket and MAK, here is a book that you will enjoy.

(An introduction to Tiger’s Tale, the autobiography of Nawab of Pataudi, can be found here.)

—

Pataudi: Nawab of Cricket

Suresh Menon (Editor)

2013

Harper Sport

186 pages; 499 Rs.

Tales of the Prince Charming of Indian Cricket | Bagunnaraa Blogs

[…] Jampala Chowdary (This article is being published on the second death anniversary of Mansoor Ali Khan Pataudi) Last […]

Jampala Chowdary

Found the following on the net with regards to the history of the Pataudi Jagir:

Pataudi was ruled by Barench clan which had control of territory between Kandahar and Pishin, about 1000 years ago. Salamat Khan came to India in 1480 and was responsible for subduing Mewati uprising and ruled over Bala Hisar. General Lake, in 1806, granted Fa’iz Talab Khan, the Pataudi Ilaka in perpetual jagir, with full judicial and revenue powers. The state ranked 17th in the Panjab Darbar (1890). The rulers were…

Nawab FA’IZ TALAB KHAN, 1st Nawab of Pataudi 1804/1829, married the sister of Najabat Ali Khan, Nawab of Jhajjar, and had issue. He died 1827 or 1829.

Nawab MUHAMMED AKBAR ALI KHAN, 2nd Nawab of Pataudi.

All the successor male children since then seem to have included Ali Khan in their names.

The income of the Pataudi jagir was listed at Rs. 160,000 in 1892 and the Privy Purse was Rs. 48,000

Also, found on the net that the Pataudi palace is now a hotel.