In Abbas’s Ghar

Written by: Ahmer Nadeem Anwer

(This is an article on K.A.Abbas, written by his grandson. We thank him for giving us permissions to republish the article on pustakam.net. This is a slightly modified version of the original article that appeared in Bihardays.com, as a part of K.A.Abbas centenary commemoration essays. – pustakam.net)

******

My working connection with the honorand was as a child actor in his film Hamara Ghar, yet in fact the association with him was deeper, more global and more extensive, even lifelong. Khwaja Ahmed Abbas, whom all in our home knew simply as “Mamoo Bachhoo” (he being my mother’s uncle), was a part of my birth family’s world for as long as one can remember. In the 1950s my parents had worked as translators in Moscow, bringing the great fictional classics of 19th century Russia to Urdu readers. This was the very time that Raj Kapoor’s Awara, penned by Abbas like the bulk of Kapoor’s finest films, had gained a kind of cult popularity in Russia, taking to new heights the Hindi-Russi love affair of the period. Everyone hummed “Awara hoon” in the streets of Moscow. In this atmosphere of warm and coruscating good relations and feelings, Abbas launched his Indo-Soviet production Pardesi, based on Renaissance merchant and traveller Afanasy Niketan’s sojourn in India. Afanasy’s love affair with a young woman hailing from his adopted country served as a metaphor of the special and enduring relationship between the Russian and the Indian peoples.

During part of the filming Abbas spent time in Moscow, and this was when he became a ‘presence’ in our home – a phenomenon that was to last decades. During off hours, he and occasionally crew members would converge at our place, among them Nargis, and the author-filmmaker would conjure up his trademark culinary concoction, which consisted in cooking a mound of vegetables, meat and rice, hurled all together inside a large cooking utensil. I of course was too young to remember such apocryphal details which I only heard later at ‘second hand’, and I don’t really have a very clear recollection of him from this time. However, the indelible awareness of Abbas, a sense, not to say sensation of him as a special and unusual person, had already taken root.

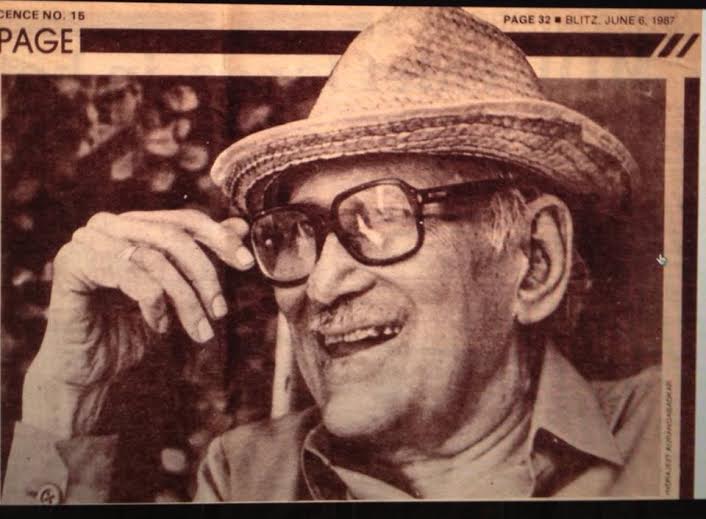

Over time, that early and amorphous, yet somehow mysteriously powerful impression began to gather flesh and a kind of compelling specificity. My parents returned to India in 1960, and after some curious perambulations my father relocated to Bombay as editor of the Urdu edition of Blitz, for which Abbas contributed one of the longest running of commentative columns, the celebrated, and often searingly unsparing ‘Last Page’. In Urdu it appeared under the rubric of ‘Azad Qalam’, which is as good a sobriquet for Abbas’s intrepid journalistic life as any that could be found. The spirit of liberty breathed in his pen. It was indeed the commitment to certain core values, among them the ideal of egalitarianism, the primacy of an engaged and combative authorial pen, the sense of membership of the progressive writers’ tryst with a socially committed inscriptional destiny, a non-negotiable investment in the idea of a secular and pluralistic India welcoming of, and just and fair unto all its constituents and peoples, including those from different faiths or no faith – all this created a special bond of shared beliefs between Abbas and my father Urdu author Anwer Azeem, so that my father’s work as founder editor of Urdu Blitz and Abbas’s ‘Azad Qalam’ led a parallel life of partnership and solidarity that matched their mutual affection, comradeship and fellow feeling.

Over time, that early and amorphous, yet somehow mysteriously powerful impression began to gather flesh and a kind of compelling specificity. My parents returned to India in 1960, and after some curious perambulations my father relocated to Bombay as editor of the Urdu edition of Blitz, for which Abbas contributed one of the longest running of commentative columns, the celebrated, and often searingly unsparing ‘Last Page’. In Urdu it appeared under the rubric of ‘Azad Qalam’, which is as good a sobriquet for Abbas’s intrepid journalistic life as any that could be found. The spirit of liberty breathed in his pen. It was indeed the commitment to certain core values, among them the ideal of egalitarianism, the primacy of an engaged and combative authorial pen, the sense of membership of the progressive writers’ tryst with a socially committed inscriptional destiny, a non-negotiable investment in the idea of a secular and pluralistic India welcoming of, and just and fair unto all its constituents and peoples, including those from different faiths or no faith – all this created a special bond of shared beliefs between Abbas and my father Urdu author Anwer Azeem, so that my father’s work as founder editor of Urdu Blitz and Abbas’s ‘Azad Qalam’ led a parallel life of partnership and solidarity that matched their mutual affection, comradeship and fellow feeling.

Such friendships, indeed, were part of the history of a time, the history of a nation still in a process of becoming and making its choices of character and identity, and hope and promise had yet to vanish from the dreams of the dedicated. Perhaps this was the reason that my father, a bon vivant who like Abbas was serious about the things he valued, but not so much as to lack a sense of humour about it all, found in the latter a kindred spirit and a mentor he could both honour and enjoy. Though Abbas was my mother’s uncle on the maternal side, he and Anwer Azeem had a separate and independent relationship of their own, and in some ways I benefited from this double connection.

Not long after we moved to Bombay in 1963 a complication arose. I had found the whirlwind peregrinations from Moscow to Delhi to Aligarh, then back to Delhi, and thence to Mumbai/Bombay to be more than I could cope with, and, after jumping a class, managed the rather remarkable feat of flunking every subject on the report card. After struggling to make a go of my study life with some solid practical tips thrown by my mother’s wonderfully benevolent aunt ‘Apa Chhadi’, suddenly a situation developed that would throw this uncertain fledgling academic career into a fresh crisis.

At this time I was staying back for extra classes at Besant Montessori in hopes of pulling up my frankly desperate grades, and would repair thence to the Abbas home in Juhu nearby. Just then a scheme was tabled, I’m not sure how or whence. It seemed K. A. Abbas wanted to cast me in a forthcoming film and the carrot dangled was that the part was to be a pivotal one in the production. In Bombay, at least in those circles, the talk was all about movies, and the prospect of being a ‘hero’ in one, albeit a juvenile one, was a temptation not easy to dismiss. Unsurprisingly, I bit, having no idea how I’d manage to balance my precarious study life with the film’s shooting, which was to take some four or five months, mainly on Madh Island in the city’s suburbs. That Abbas had recently won the national award for best film of the year for Shehar Aur Sapna (a film where also the struggle for a “ghar” was centrestage) clinched matters as far as I was concerned.

At this time I was staying back for extra classes at Besant Montessori in hopes of pulling up my frankly desperate grades, and would repair thence to the Abbas home in Juhu nearby. Just then a scheme was tabled, I’m not sure how or whence. It seemed K. A. Abbas wanted to cast me in a forthcoming film and the carrot dangled was that the part was to be a pivotal one in the production. In Bombay, at least in those circles, the talk was all about movies, and the prospect of being a ‘hero’ in one, albeit a juvenile one, was a temptation not easy to dismiss. Unsurprisingly, I bit, having no idea how I’d manage to balance my precarious study life with the film’s shooting, which was to take some four or five months, mainly on Madh Island in the city’s suburbs. That Abbas had recently won the national award for best film of the year for Shehar Aur Sapna (a film where also the struggle for a “ghar” was centrestage) clinched matters as far as I was concerned.

The planned new film spoke volumes about the kind of filmmaker, and indeed the kind of man, Abbas was. He was more than offbeat; he was a movieland maverick who took unimaginable commercial risks with his films, mostly financed from earnings from his indefatigable journalistic labours. Nobody made movies about or with children in Bombay cinema proper. Yet Abbas, going against the grain, had already experimented with feature films centered on child protagonists, such as the highly acclaimed Munna, as well as the idea behind Boot Polish, scripted by him for RK. However, in Hamara Ghar, Abbas would go still further and depart from the Bollywood norm altogether, by choosing to make a full-length feature with an all-juvenile cast. To create an entire world populated exclusively by children, they would have to be ejected literally out of adult-constituted mainstream society as we know it.

In 1954, the year of my birth, the English novelist William Golding had published his classic Lord of the Flies which went on to earn its author a Nobel Prize for literature; in 1963 the novel was filmised and drew critical notice at Cannes. The narrative action of Lord of the Flies, owing something to children’s adventure tales such as Coral Island yet vastly different in tone and outlook, takes place against the imagined outbreak of nuclear war in Europe. A bunch of English schoolboys have been evacuated to a desert island in hopes of escaping the holocaust, and the story traces their efforts at preserving their reliably solid British liberal and honourable boy-scout training heritage in the ‘new world’, wherein they find themselves. As it turns out, the efforts of a minority of the children to live decently and in a spirit of sharing and camaraderie come a-cropper pretty soon, thanks to the speedy ascendancy of seething atavistic drives that surface when those young persons are placed in a “state of nature”. Golding’s sense of basal human nature as embodied in the child is disturbingly counter-Rousseauvian and dark.

As some of those marooned and societally deracinated children regress to brutal power struggles and efforts at dominance, narcisstic self-aggrandisement, and, in the end voodoo ritual worship and cannibalisitic feeding on their weaker fellows, the point is made clear: the reason fascism, or nuclear holocaust, can become real in adult Europe, is that those adults merely play out on the platform of sophisticated technology the dark instincts of the children they once had been… Life and human instinct are Hobbesian, a relentless and unsparing war of each against all, and children’s instincts are as beastly as those of their more technologically equipped elders. Humanity’s chances, given such a profoundly gloomy envisioning, would appear to be bleak….

Abbas took on this sinister reading of human nature and especially of the nature and inclinations of children.

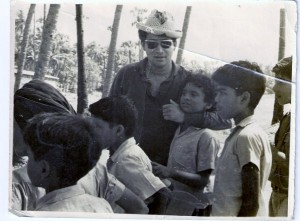

In Hamara Ghar (1964) [The picture to the left is from the movie shoot], which is clearly designed as a systematic and principled counterblast to the radical anti-humanism of Golding’s vision but sharing many structural, situational and plot homologies with the latter’s unsettling novel, Abbas creates a meta-comment that implicitly re-reads Golding’s narrative as a kind of bestial and tendentious, and no doubt scripturally shadowed, canard on the root ‘evil’ of the human species itself, as embodied in the ‘ignoble savagery’ of childhood.

In Hamara Ghar (1964) [The picture to the left is from the movie shoot], which is clearly designed as a systematic and principled counterblast to the radical anti-humanism of Golding’s vision but sharing many structural, situational and plot homologies with the latter’s unsettling novel, Abbas creates a meta-comment that implicitly re-reads Golding’s narrative as a kind of bestial and tendentious, and no doubt scripturally shadowed, canard on the root ‘evil’ of the human species itself, as embodied in the ‘ignoble savagery’ of childhood.

I suspect there were many reasons for Abbas’s metatextual attitude. For one thing, I think he really liked children, enjoyed their company, their chatter, their dreams, their fears and hopes. I haven’t met too many adults, especially males, who could really talk and interact with persons half a century younger the way he could. For another, I think that he, like Golding, yet in a diametrically different way, saw the child as the key to the propensities of humanity at large, and to the prospects of modern mankind on a nearly prophetical level. In particular, after the internal holocaust and civil butchery of Partition – the parallel to Europe’s nuclear crisis in Golding – India then was struggling to offer to the world the image of a society that could overcome a terrible history of fissiparous internecine hostilities and violence, and essay a fresh beginning that would help it to survive in a spirit of acceptance, coexistence and altruistic affirmation of its different ethnic and religious groupings, real difficulties notwithstanding. One wouldn’t pretend the difficulties out of existence, but one might confront and tame them. Perhaps a band of children could offer to the adult world a lesson worth learning.

Hamara Ghar takes the Lord of the Flies situation, and imparts to it a very different unfolding and denouement – an altogether variant ‘edge’. A group of schoolchildren are to go by steamer on a fun-trip to Goa; but en route things start to go wrong. A turbulent sea storm flings their rescue lifeboat upon a desert island, stranded on which they must now attempt to survive unaided. The struggle for survival, as in Golding, entails not merely surviving the beasts and manifold dangers of the forest and sea, or the securing of food and habitation, but more importantly, taming the beast within.

Abbas declines to accept Golding’s presumption of a Calvinistic sin-proneness within every human child and heart. But his less theological, more ‘socialised’ envisioning of our behaviours does contend with the reality that society and its forces seem divided up between on the one hand decently inclined and gentler beings, who often end up dominated and disempowered, and, on the other hand, the more openly bellicose and domineering drives and ambitions of those seeking unbridled power and a monopoly of advantage and surpluses. In the film, the latter tendencies are personified through the oldest of the male children (who is a chronically class-repeating young man, in fact, a dandyish chap born with a silver spoon, whose identity from the beginning rests on a pride of acquisitions and rank based on status symbols and unabashed conspicuous consumption).

Abbas is concerned to show that the idea that some can bully and rule the roost must be ruinous when life is pared down to the basics: a band of school kids sourced from different strata, regions, religions and genders and needing to cohabit and pull together can no more afford such power plays and animosities than can a nation and subcontinent of hundreds of millions. Some other principle of living must be found or fashioned. And while fortunately the rage of dominance, greed and megalomania infects only a minority of the marooned children, many more are susceptible to the would-be exploiters’ blandishments, cunning divisive ploys, and plain blackmailing and bullying tactics.

Yet Abbas does not, in the end, show the malefactors succeeding, and his band of stranded survivors do manage to find their way out of the looming maelstrom, thus avoiding the inescapability, in a sense, of the fate of Golding’s youngsters, who must both literally and metaphorically feed and prey upon one another, as their ‘inevitable’ perceived modus vivendi and means of survival.

How is this avoided? It requires a human agency – an intervention by somebody who cares, and understands enough to bother and try to make things work just when nothing seems to. This blood-bath averting agency was assigned to a boy who on the face of it seemed an unlikely choice, lacking as he does the advantages the other children can take for granted. It is a motherless Dalit boy who has been able to finance his trip only by his extra hours as a shoe-shine (the work with which he funds his studies too). It is this boy who in the film embodies the defiance of those who shall not accept their exclusion from education, work, self-respect – or even recreation and pleasure: this is his father’s bequest to the boy, Sonu, and the son takes his blind, yet all-seeing, all-understanding Tiresias-like father’s message seriously. And so he joins the band of boys and girls on the missed Goan holiday. Children who end up, trying like India itself since 1947, to muddle through an uncertain tryst with destiny under often insalubrious challenges.

The critical point is that Sonu, being who he is, has perhaps more stakes in the survival of the cooperative-supportive vision of sociality and communal living, than do some of his more privileged schoolfellows. And so when, egged on by Ghanshyamdas Sonachand, the sneering, swaggering scion of a filthy rich clan, the children have been pushed to the brink of destroying their collective home and habitation, their “hamara” ghar, Sonu confronts the mob and attempts to reason and argue with them. Reason, though, is a weak brake upon unleashed fury and ‘emotive’ arousal by clever manipulators of people’s emotions and insular ideas of self-advantage, and it takes the flow of empathy for a nearly drowned Sonu to return the hyper-incensed children back to their senses. One near-death experience, though, is enough to remind them that not just their experiment in pulling together with decency and mutual caring, but life itself was now at fatal risk, and a decision must be made. Luckily, they decide in the least damaging way. As in Golding, the children are ultimately rescued – but unlike in Golding sufficiently in time for utter horror to be averted.

I played the part of Sonu who helps obviate horror. I don’t believe Abbas chose me for the role because he thought I had some histrionic ability that the others did not: some of the youngsters, such as Noel who shinnied up coconut trees at top speed, or Larry, the Jewish boy who later migrated to Israel, had undoubtedly more acting talent than I, and they showed it on screen in slimmer parts. The reasons I landed the plum role were twofold (I suspect). First, although Abbas deplored the implicit hierarchies of the star system, he was nonetheless secretly partial to those he loved, befriended and was close to in real life, and often cast the children of close associates in meaty parts in his movies – and serendipitously, some of those so favoured went on to prove what stellar talents they really were (not I, but I’m thinking of some really famous names).

In that set of children who were cast in Hamara Ghar, I just happened, by virtue of my parentage, to be the most closely associated and related! Second, although no great actor, I, a person who never essayed an acting attempt before or since, seemed for some reason to fit his imagination of the part and plot function he meant to be assigned to Sonu. A close view of the matter might say that Sonu is somewhat too good to be true for a child, talks and preaches in fulsome moral sermons, and while he can be victimised, he cannot counterattack. His near tragedy, or his near martyrdom, is what saves the children from regression to hell and nightmare, but such moral leadership verges on hyper-idealisation and a goody-two-shoes simplicism and naivete. In general, Abbas’s films were designed by very clear moral antinomies, almost on the pattern of a Morality Play, where demons and good angels play out clearly divided parts, and characterological ambivalence and complexity are a rarity.

All this may contain a grain of truth, but in Hamara Ghar it may have been necessary. I did hear that Abbas commissioned the leading Urdu fiction writer Krishan Chander to sculpt the part with me in mind. And yet, strangely, though I was nowhere near being the ideal, totally ‘good’ and fault-free child Sonu is, there were a few homologies of temperament and outlook; at any rate the moment when Sonu finally loses his cool and plunges into the waters biting back his tears yet staying angry and defiant, used something I used to have as a child and young person. In this, Abbas and Chander (both knew me and Krishan Chander had evidently been sharply briefed) were uncannily perceptive and observant.

In retrospect, I’ve sometimes wondered, how much of myself went into the delineation of Sonu, and how much of Sonu, consciously or unconsciously, helped shape me? Critics were kind, and the reviewer of the Times of India Bombay edition forecast for me (inaccurately so) a bright child-actor career, but actually I was mostly playing myself (being way too young to ‘think’ through the matter), and the casting instincts of Abbas in that sense were the main reason why it may have come off for me.

Looking back, it was an extraordinary learning experience. I have never lived in quite this way, with such a sense of community, among peers of so many kinds, such wide gaps and differences of age, group identity and cultural background notwithstanding. In a very real sense, Abbas recreated on location and during the filming the very ideals of mutuality, reciprocity and altruistic-cooperative community living which he made the conceptual principle of his narrative. Each morning, a ramshackle half bus would wind its way across town picking up child after child – no one found any special favours there, and I as a family member got none either. So about four hours of the day we were in transit, making for a long but productive working day, punctuated by songs, dances, impromptu wrestling matches, and community lunches in which everyone, the director included, joined in without the slightest element of hierarchy or stuffiness. (At times things could go too far in this direction though, as when the socialistic sharing out of realistically unwashed shorts triggered an outbreak of jock itch among the juvenile cast members, my own self included!)

This went on, day after day, in an unbroken rhythm for the entire duration of the filming, though my mother did come on the set a few times to help me with my books for the school test, and also when the nocturnal storm scene was to be filmed (I fell asleep cold and exhausted, and Abbas seized the opportunity to filmise me in a realistic state of post-drowning ‘unconsciousness’!).

However, Abbas’s obsessive penchant for ‘realism’ did result in one skirmish between him and myself. At the point where Ghanshyam leads an angry and violent mob to wreck the collective home of the children, a shack made with love, care and hard work by themselves, the ten year old Sonu steps in their path. Ghanshyam thrusts aside the younger boy and rushes forward leading the others, and Sonu is sent hurtling – they just jump over his prone form. I was instructed to ‘mime’ the fall when I’m lightly pushed.

But privately Abbas instructed Ghanshyam to hit and push me as hard as he could. At an athletic eighteen or nineteen years Ghanshyam was already a young man, and eager to prove his pugilistic prowess and possibly carried out his instructions with even greater enthusiasm than the director had in mind. Be that as it may, I was sent flying and crashed my head against a tree with some considerable force. There was a heavy concussion of the head, I blacked out, and the headache lasted days. But more than the physical injury, it was the shock of “betrayed trust”, the sense that I’d been deliberately set up and made a fool of, that upset me most, and I threatened to quit the film midway, because I felt that ‘Mamoo Bachhoo’ for the sake of his blasted realism had put my safety at risk, but even more so, had taken unfair advantage of my young trust.

To his credit, he came home a few days later, on Diwali, and tendered his apologies along with a generous supply of sweetmeats, and even some festival time gift money, though remuneration was no part of the deal. Of course I’d known all along that I’d eventually relent, although I was hurt and furious, since I did not plan to ruin the film, much of which had already been filmised, and this gesture on his part was enough to open the way to the truce that led to a peaceable conclusion of the film’s making. When it opened in a theatre the name of which I now forget, I was thrilled, jumped forward to shake as many as possible of the first show viewers’ hands, and walked around on a cloud for a while.

When the film was screened at Rashtrapati Bhawan in Delhi, and my sister and female cousins set up a boohooing wailing “Pasha doob gaya, Pasha mar gaya”, I presented myself to them with something of a dramatic flourish after the show was over, grinning widely and pleased as punch with a scale of importance I’d never before enjoyed. That Abbas trusted me enough to give me the part gave me a surge of confidence, and in the glow of all that I even finally forgave him the tree bump! Soon, the sober realities of life, study and work took over, pushing filmland and its wonders firmly to the background, and I continued my journey to my life as a student of literature and a pedagogue, which has its pleasures and compensations, though the arc lights and public notice are not among them…Sometimes, when I read lines from a play in class, or a powerful passage in a poem, I recall with a touch of affection and nostalgia, my brief brush with acting, and remember the man who made that possible…

Many years later, I renewed with Abbas one more working encounter, though briefly and limitedly. I had recently joined the teaching profession after finishing my Master’s, and Abbas was doing a book project on the Emergency. This strange rupture in free India’s democratic history helped politicise me, as well as my response to my academic discipline, literary studies. I was nothing if not scathing on this quasi-fascistic interregnum with its suspension of civil liberties and citizen rights, and the neutralization, often in jails, of a political opposition.

Abbas was a little taken aback by the vehemence of what I said I think. His own allegiance to Nehru and by extension Nehru’s daughter made it difficult for people like him (and my father) to quite make sense of what had happened within their conceptual, but also their emotional frame. But I quickly realised then that my great-uncle was a rigorous, and rigorously honest researcher and journalist, for he could set aside his own mental habits sufficiently to really listen and connect to a different view, even if this upset many verities that he had taken for granted all his life.

At that moment to the qualities I’d always known in him – his courage, his indomitable spirit and fierce defiance, his good humour and wit and his bon vivant charm with the ladies (I’d witnessed some of that magic during after preview dinners at Moti Mahal in Delhi), was added yet another, and one that arguably may have been K. A. Abbas’s greatest quality: unswerving intellectual and professional integrity. This was a special person indeed, and I was privileged to know him.

Of course, he wasn’t without contradictions, which only made him human. He theoretically despised the star system, yet he secretly had his favourite stars; for instance his unquestioning loyalty to Raj Kapoor. He also had his favourite actress, also a big star in Bombay. On Children’s Day during the shooting of Hamara Ghar, a snow white Mercedes Benz drew up at the seaside location where the film’s action was shot. Out of the car emerged Meena Kumari like some ethereal deity from a magic chariot. We were mesmerised, little knowing that this acting genius had only recently completed her life’s crowning acting triumph in Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam. The great actress insisted on knowing “film ke hero kaun hain?” Abbas for his part insisted that his film had no hero and no heroine, and as in Orwell’s Animal Farm, all the child-animals were equal. But she would have none of it, and in the end he grudgingly looked my way. She drew me to her and tousled my hair for a bit, and I smiled shyly at her, and then glanced gratefully at K. A. Abbas for breaking his rule. I had, for a moment, been touched by divinity.